Biography of Dr. Breckinridge, William Norwood, 1875-1949

Item

- Title

- Biography of Dr. Breckinridge, William Norwood, 1875-1949

- Date

- n. d.

- Description

-

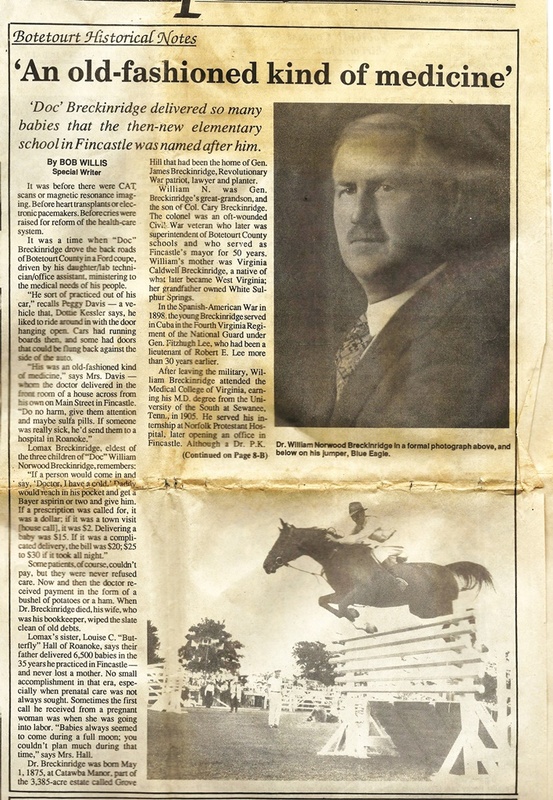

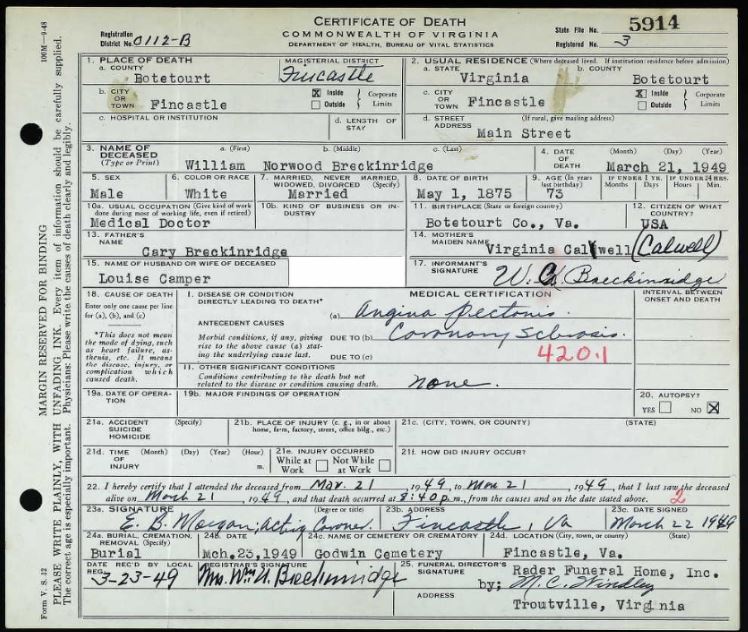

Article titled "An old-fashioned kind of medicine" detailing the life of Dr. William N. Breckinridge, who lived from May 1, 1975 to March 21, 1942 and is buried at Godwin Cemetery.

The third image is his death certificate.

The article reads,

"An old-fashioned kind of medicine.

'Doc' Breckinridge delivered so many babies that the then-new elementary school in Fincastle was named after him.

It was before there were CAT scans or magnetic resonance imaging. Before heart transplants of electronic pacemakers. Before cries were raised for reform of the health-care system.

It was a time when 'Doc' Breckinridge drove the back roads of Botetourt County in a Ford coupe, driven by his daughter/lab technician/office assistant, ministering to the medical needs of his people.

'He sort of practiced out of his car,' recalls Peggy Davis - a vehicle that, Dottie Kessler says, he liked to ride around in with the door hanging open. Cars had running boards then, and some had doors that could be flung back against the side of the auto.

'His was an old-fashioned kind of medicine' says Mrs. Davis - whom the doctor delivered in the front room of a house across from his own on Main Street in Fincastle. 'Do no harm, give them attention and maybe sulfa pills. If someone was really sick, he'd send them to a hospital in Roanoke.'

Lomax Breckinridge, eldest of the three children of 'Doc' William Norwood Breckinridge, remembers:

'If a person would come in and say, "Doctor, I have a cold," Daddy would reach in his pocket and get a Bayer aspirin or two and give him. If a prescription was called for, it was a dollar; if it was a town visit [house call], it was $2. Delivering a baby was $15. If it was a complicated delivery, the bill was $20; $25 to $30 if it took all night.'

Some patients, of course, couldn't pay, but they were never refused care. Now and then the doctor received payment in the form of a bushel of potatoes or a ham. When Dr. Breckinridge died, his wife, who was his bookkeeper, wiped the slate clean of old debts.

Lomax's sister, Louise C. 'Butterfly' Hall of Roanoke, says their father delivered 6,5000 babies in the 35 years he practiced in Fincastle - and never lost a mother. No small accomplishment in that era, especially when prenatal care was not always sought. Sometimes the first call he received from a pregnant woman was when she was going into labor. 'Babies always seemed to come during a full moon; you couldn't plan much during that time,' says Mrs. Hall.

Dr. Breckinridge was born May 1, 1875, at Catawba Manor, part of the 3,385-acre estate called Grove Hill that had been the home of Gen. James Breckinridge, Revolutionary War patriot, lawyer and planter.

William N. was Gen. Breckinridge's great-grandson, and the son of Col. Cary Breckinridge. The colonel was an oft-wounded Civil War veteran who later was superintendent of Botetourt County schools and who served as Fincastle's mayor for 50 years. William's mother was Virginia Caldwell Breckinridge, a native of what later became West Virginia; her grandfather owned White Sulpher Springs.

In the Spanish-American War in 1898, the young Breckinridge served in Cuba in the Fourth Virginia Regiment of the National Guard under Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, who had been a lieutenant of Robert E. Lee more than 30 years earlier.

After leaving the military, William Breckinridge attended the Medical College of Virginia, earning his M. D. degree from the University of the South at Swannee, Tenn., in 1905. He served his internship at Norfolk Protestant Hospital, later opening an office in Fincastle. Although a Dr. P. K. Graybill also practiced in the town then, says Lomax Breckinridge, for many years his father was the only physician there.

On Nov. 14, 1914, Dr. Breckinridge married Louise Camper, daughter of Clinton Belle Camper, owner of the Fincastle Herald. They lived at Aspen Hill on Main Street, so named because of the large aspen trees on the property. (As a boy, Lomax helped plant a pecan tree, now about seven feet in diameter, at the home.) The couple had three children; the second son, William Cary of Fincastle, died last June 18.

For many years Dr. Breckinridge had a clinic in his home. Earlier, he maintained an office on Roanoke Street, between the present Bank of Fincastle and what was then The Herald office.

However, he was not always to be found there. Those were pre-television days, and, says Dottie Kessler of Fincastle, when men of the town had nothing else to do, they might hang out with each other and talk. The doctor, says Peggy Davis, could often be seen on the street near the courthouse. Knowing he was there, the central telephone operator would lean out of her second-floor window and say, 'Doc Breckinridge, you're wanted at the Smiths,' or wherever.

Not only the doctor could receive such a summons, relates Dottie Kessler. The operator could see everything from her listening post, and a mother might ring her up and say, 'Miss Julie [Austin]? (or Miss Minnie [Crowder]?) Do you see Jimmy? Would you tell him to come on home?'

More than one generation has called Mrs. Hall 'Butterfly' without knowing why. 'I got that nickname,' she says, 'when I was about three years old. We had a servant that was the husband of the cook. He was taking me for a walk one day, and Mother, I guess, had a great big bow on my then-blond curls, and I was running ahead of him. When we came back he said, "Miss Louise," to my mother, "we will have to get another name for little Miss Louise. It's too much for me to say."

'She said, "George, why don't you think of a name?" He said, "Well, I have one in mind. It's Butterfly, because she looks like one today." And Mother said, "Well, I'll have to speak to Dr. Breckinridge about that." They discussed it, and they loved George so much, and they decided on it. And' - laughing - 'it's lasted all these years.'

She never outgrew the nickname, but 'Butterfly' did grow up to enter Farmville State Teachers' College. After a year there, she decided she preferred medicine and was able to enter nursing school at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. She had not been there long before she caught a strep germ from a patient (who later died), and was kept in isolation for two months, then sent home to rest.

She felt better after a couple of months and, rather than return to school, went to work in 1939 for her father as a laboratory technician and office assistant, which she did until the end of his days.

'Dad was getting on in years then - he was 40 when he married - and I wanted to help him. I just admired, adored and worshiped him, and wanted to make him proud of me. I think it was a disappointment to him that none of us followed him into medicine, and although I was interested in doing the things I did, I was disappointed in giving up a profession of my own.'

Starting at age 14, she was also Dr. Breckinridge's chauffeur - he didn't like to drive, and burned out a lot of clutches. She drove him to house calls everywhere he went. 'We went into Craig County, too. We forded many a stream.'

Lomax Breckinridge says their father owned one of the first automobiles in Botetourt County. 'He never bought anything but Ford products' - most of them from Fincastle Motors. In the early days, automobiles might have to be started with a hand crank, which could kick back with damaging effect. Dr. Breckinridge had to set more than one arm broken from this recoil.

The physician kept horses (named Mesach and Radium) and a buggy in a stable below the house to drive in winter. But in good weather he used his car. Once, the story goes, he was tooling down a rural road in his auto when he encountered a farmer driving a pair of mules.

The animals, spooked by this strange vehicle, broke loose from the wagon and bolted, all the way into Craig County 12 or 14 miles away. 'Don't put his name down,' says Mrs. Hall, 'but he never spoke to Daddy again.'

Among the thousands of babies her father delivered was a tiny girl surnamed Mullins, weighing 22 ounces. The mother, who lived at Stoney Battery, didn't want to go to the hospital. So the doctor found a wet nurse and kept the baby swabbed down with cotton and warmed with hot-water bottles. The infant survived, says Mrs. Hall, to become a precocious child and, at 18, wrote Dr. Breckinridge a letter thanking him for saving her life, 'with the help of the Lord.'

Dottie Kessler also recalls that the doctor suggested names for some babies he delivered. One boy, born during a severe winter, was christened Eskimo.

Dr, Breckinridge owned two small farms, about 50 acres each, outside town; one for pasture and hay, the other for livestock. At one of these was born a colt he named Blue Eagle. When the young horse leaped over a fence, the doctor exclaimed, 'What a jumper!' and proceeded to train the prized animal in the specialty.

'He took him to all the shows in North Carolina and western Virginia,' says Lomax Breckinridge. 'He finally sold that horse to a lady named Elizabeth Whitney from Upperville, Va.' She showed the gelding, then about six or seven years old, at Madison Square Garden in New York where he won honors. But, relates Mrs. Hall, a drunken driver struck Blue Eagle coming out of the paddock there, breaking his leg, and the horse had to be destroyed.

Like his father, Dr. Breckinridge was an ardent Democrat, serving several times as party chairman in Botetourt County. Starting in 1924, he attended a number of Democratic National Conventions.

At the 1940 convention in Chicago, says Lomax Breckinridge, Virginia Democrats nominated Harry Flood Byrd as a favorite son. When Byrd's name was presented for the presidency, says Lomax, Dr. Breckinridge 'had his beautiful nice [Lucille Breckinridge, who lived in Chicago] loose about 20 doves in the convention hall.' The birds symbolized the senator's name.

The doctor served with the Medical Corps at Hampton during World War I, but was allowed to return to Fincastle to attend to victims of the 1918 influenza epidemic. (That outbreak killed some 20 million people worldwide, an estimated 675,000 in the United States.) After Selective Service was reintroduced in 1940, he became the examining physician for inductees in Botetourt, as well as for some of the overflow from Roanoke. 'I remember you stickin' me' for the blood test, some would tell him years later.

Dr. Breckinridge was a member of the Electoral College in 1948, but his Selective Service duties prevented his casting a vote for Harry S. Truman. Mrs. Hall succeeded him, becoming what a Roanoke World News photo caption called the first 'Electoral College coed.' Her father would later attend Truman's inauguration. The doctor sought elective office himself once, in 1939 in the 20th state senatorial district; he was defeated by a cousin, Tom Wilson, a Republican from Clifton Forge.

He was an imposing figure, 'a great force of nature,' remembers Peggy Davis, who as a girl was somewhat awed by him. Lomax Breckinridge describes him as stand-"

Captions of photographs read,

"Dr. William Norwood Breckinridge in a formal photograph above, and below on his jumper, Blue Eagle."

"'Doc' Breckinridge's son, Lomax of Fincastle, in front of a portrait of his ancestor, Gen. James Breckinridge, who built Grove Hill near Fincastle in the late 19th century. James Breckinridge's law office is now the Botetoort [sic] County Museum." - Grave marker

- Creator

- Willis, Bob.

- Format

- image/jpeg

- Subject

- Grave marker

- Gravestone

- Headstone

- Godwin Cemetery

- Fincastle

- Breckinridge School

- Type

- Text; Image

- Publisher

- The Fincastle Herald

- Coverage

- Fincastle, Botetourt County

- Rights

- http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/

- Item sets

- Community

Position: 46 (76 views)